You Never Know When You Are Making History

Making history can seem easy, especially when, with the click of a mouse, we can quickly find those who’ve done so. However, it takes a lot of hard work to make history, and the impulse to do so is often rooted in an outcry for change or inclusion or simply being seen and heard.

Women seem to get that — especially those called into nursing.

Nursing is the largest profession in the American healthcare system and is the pillar of the U.S. healthcare industry. For the 20th year in a row, it is also the most trusted healthcare profession. With over 3 million nurses providing care, it is inspiring to know that there have been many greats who made it possible for our millions to carry on the torch.

In honor of Women’s History Month, I wanted to look at some of the firsts and some of the famous women who’ve contributed to the profession’s development, groundbreaking procedures and breaking barriers.

Knowledge Is Power

In 1878, 42 students entered a rigorous program that The New England Hospital for Woman and Children’s nursing school offered; by 1879, only four remained. One of those four was Mary Eliza Mahoney. She became the first African American woman to be a licensed nurse in the U.S. Alternatively, thanks to a 1902 Rochester, New York meeting, which crafted the Nurse Practice Act, nurse and midwife Ida Jane Anderson became the first registered nurse in New York state after graduating from the Rochester Homeopathic Hospital School of Nursing.

In September 2021, Google Doodle highlighted Latina nurse and trailblazer Dr. Ildaura Murillo-Rohde to kick off U.S. Hispanic Heritage Month. A Panamanian American, Murillo-Rohde founded the National Association of Hispanic Nurses (NAHN) and served as its first president. Focused on improving the healthcare system for the Hispanic community, NAHN is the leading professional society for Hispanic nurses and was created to serve needs that the American Nurse Association (ANA) wasn’t meeting. In 1971, she became the first Hispanic nurse to earn a doctorate from New York University.

Meanwhile, Susie Walking Bear Yellowtail — the “grandmother of American Indian Nurses” — became the first registered nurse from the Crow Nation and first Native American in the U.S. to earn a nursing degree.

It’s exciting to wonder whether when those women began their journeys to serve others that they knew they’d be a first and, in some cases, an only.

Going to Battle

History likes to point to the more famous Florence Nightingale (1820-1920) as the founder of modern nursing and for her work in the Crimean War. We should also be as familiar with British-Jamaican Mary Seacole (1805-1881), who was an unofficial nurse to Crimean War soldiers. While Nightingale was astronomically instrumental in pinpointing lifesaving sanitation methods and the invention of a polar area diagram used to measure mortality causes during her 1854-1856 participation of the war period, Jamaican born Seacole had no formal nurse training and relied upon herbal medicines and knowledge from her doctress mother to care for the British soldiers. Despite the high accolades she earned while treating an 1850 cholera epidemic, Seacole was told she would not be offered a position to nurse — even if one became available. On their own dime, Seacole (also a traveler and entrepreneur) and a partner established the British Hotel and created their own facility for the sick and wounded while also traveling on horseback two miles away to help stationed soldiers.

Going to battle for those in need seems to be a common theme with our nursing sheroes.

History in the Making

Lillian Wald, a Jewish woman of privilege born in Cincinnati in 1867, is known as the first public health nurse and coined the term. In 1889, Wald attended the New York Hospital’s School of Nursing; in 1891, she graduated from the New York Hospital Training School for Nurses and subsequently took courses at the Woman’s Medical College. A devoted social reformer and humanitarian, Wald advocated for women and children’s rights and served poor immigrant communities in New York City’s Lower East Side to where she eventually moved. In 1893, Wald founded the Henry Street Settlement there, which philanthropist Jacob Schiff funded. Wald also visited her patients personally, which was uncommon at the time because healthcare was usually administered at home and to those who could afford it.

Seeing a clear need that all people deserved access to healthcare, Wald suggested a national health insurance plan and also established a nursing insurance partnership with Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Wald also helped found the National Organization for Public Health Nursing and Columbia University’s School of Nursing.

Bettie Mae Tiger Jumper is another woman who worked to serve her community. As a travel nurse, she devoted her career to primarily serving the Seminole community. Both the first female chief of the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the first health director of the Seminole tribe, Jumper helped Seminole patients navigate the Western healthcare system. Florida State University awarded her an honorary doctorate in 1994. We know that women (and people in general) take action in the face of injustice, inequality or even ineptitude. We can be reminded of the work of two patriotic women, Mabel Staupers and Diane Carlson Evans.

Staupers has been recognized for her efforts to end racial discrimination among nurses; her big win occurred when the U.S. Army Nurses Corps integrated Black nurses after Pearl Harbor. After the war, Staupers continued her liberation fight and gained full membership for Black nurses in the American Nurses Association in 1949. Interestingly, both Mahoney and Staupers became ANA Hall of Fame inductees posthumously.

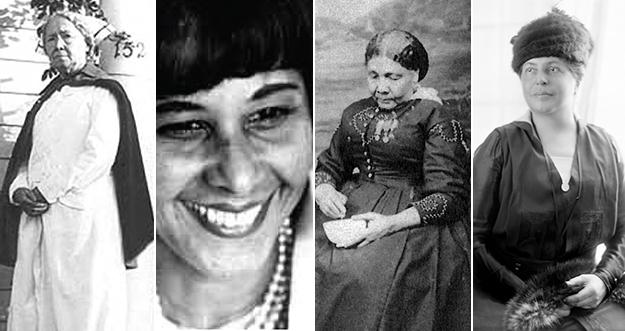

Photos: (top of page, l to r): Ida Jane Anderson, ldaura Murillo-Rohde, Mary Seacole and Lillian Wald; above: Diane Carlson Evans.)

Taking Action

Vietnam War nurse Diane Carlson Evans served as a surgical nurse in the surgical and burn unit of the 36th Evacuation Hospital in Vung Tau, Vietnam, and in the 71st Evacuation Hospital in Pleiku, Vietnam. Her service is doubly notable because she founded and became president of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial Foundation, where she championed the deserved recognition of the thousands of American military women who fought in the war. The Vietnam Women’s Memorial was finally dedicated on November 11, 1993.

There are so many nurses who have done truly amazing things, and no nurse is without meeting or overcoming a challenge — be it racial, social or operational. For example, many of you have experienced a historical victory with the signing of the safe staffing bill and winning local campaigns. Over the past two years especially, each day has been a history-making achievement. You are the ones making history now for women today and for those who are following behind you. Continue carrying on proudly.